Who was William Blake?

He who binds to himself a joy

Does the winged life destroy

He who kisses the joy as it flies

Lives in eternity's sunrise

-From Eternity by William Blake

William Blake is a difficult man to define- engraver, artist, poet, visionary, prophet, revolutionary, genius…maybe even bonafide nutter. Following an 1809 public exhibition of his works, an anonymous review appeared in the Examiner in which he was referred to as “an unfortunate lunatic”. In 1811, Robert Southey told a friend that Blake had shown him “a perfectly mad poem called Jerusalem”. And, two years prior, the reviewer writing for the Examiner about the artist's first solo exhibition had very strong feelings about Mr. Blake and his work, stating "no one can deny that his Muse has been on the verge of insanity, since it has brought forth, with more legitimate offspring, the furious and distorted beings of an extravagant imagination", and then continued by referring to him as an "unfortunate lunatic".

I don’t think Blake was a lunatic, but nor would I judge Southey too harshly for referring to his poem as mad. William Blake was indeed known to be somewhat of an eccentric. Someone once reported having seen him and his wife naked in their garden in Lambeth reciting Milton. There seems to be some doubt about whether or not this actually happened, but what is certain is that he was a fascinating, complex, and truly unique man of his time.

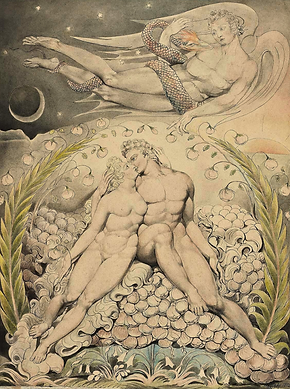

William Blake, Satan Watching the Caresses of Adam and Eve (Illustration to Milton's "Paradise Lost") 1808, Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

Early Life

He was born in London on November 28, 1757. The son of a hosier, his education occurred mostly at home with Milton, Shakespeare, and the Bible among his teachers. William showed a talent for drawing and was fortunate enough, beginning at the age of ten, to attend a drawing school for the sons of tradesmen and had ambitions to be a painter. However, he needed a more practical skill and was only fourteen when he was apprenticed to an engraver. During his apprenticeship, Blake did not give up on his more artistic aspirations, and upon finishing in 1779, he entered the Royal Academy. It was a fairly new institution at the time, and its first president, Sir Joshua Reynolds, still presided. To put it lightly, Blake disagreed with the eminent president’s aesthetic doctrines. Later in life, he wrote that Reynolds was “hired by the Satans for the Depression of Art”. Despite Blake’s difference of taste and refusal to paint in oils, his time at the Academy was fruitful, with six of his paintings accepted in the annual exhibitions during his six-year stint.

William Blake, The Witch of Endor Raising the Spirit of Samuel, 1783, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art Print Collection, The New York Public Library.

Impacts of Enlightenment, Industrialization, and Revolution

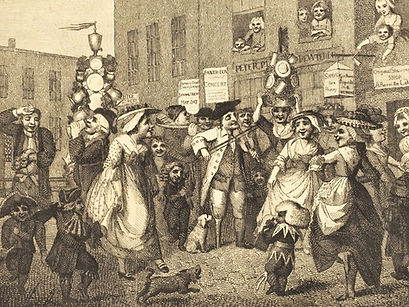

In many respects, William Blake was a man of his time. He was a product of the Enlightenment, but he was also part of a rising backlash against the cult of Reason. He lived in a London that was transforming before his very eyes. By 1700, London had become the largest city in Europe, but by 1800 it had grown exponentially, outpacing infrastructure and local government. It was dirty, crowded, and chaotic. As the center of both modern manufacturing and of an expanding empire, people were pulled into its grasp by an incomprehensible force. The streets of London were equally a workplace and the realm of scavengers and beggars. Among those trying to eke out a living in the crowded city were street performers, peddlers, prostitutes, lamp-lighters, and chimney sweeps.

William Blake after Samuel Collings , May-Day in London. Folding frontispiece to the v.1, May 1, 1784 issue of Wit’s Magazine (London, 1784). Etching.

![William Blake, Songs of Experience: London, [1794] printed ca. 1825, Metropolitan Museum of Art.](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/18d2f2_56c30add69ed4ecbbf88f2fdbddeb498~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_231,h_307,al_c,q_80,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/18d2f2_56c30add69ed4ecbbf88f2fdbddeb498~mv2.jpg)

William Blake, Songs of Experience: London, [1794] printed ca. 1825, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

What is more, events that occurred far away from the city were having a significant impact on this already turbulent city. In 1783, the British Empire lost its American colonies, which was in and of itself unpleasant. However, what was more dangerous to British order were the ideas of Thomas Paine infiltrating the shores across the Atlantic. The spectre of republicanism went from a vague, shadowy notion to an imminent threat with the onset of the French Revolution.

Blake was not alone in favoring an end to hereditary monarchy, and the existence of such sentiments would lead to years of censorship and paranoia within the government, especially in the latter half of the 1790s. It was during this era that the charge of sedition became the government's favorite tool for silencing those with radical ideas of reform. As such, in 1804, Blake was tried for sedition after supposedly yelling at a soldier, "Damn the king!" Fortunately, he was acquitted, but the ordeal never left him.

William Blake, God Judging Adam, ca. 1795, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Illuminated Printing

However, the last decade of the 18th century had been promising for William Blake. In 1788, he had a vision or a dream featuring his dead brother, who was kind enough to help him come up with a new method of relief etching that he would call “illuminated printing”. This new method allowed William to print both text and images on the same copper plate. According to him it allowed him to create a product “more ornamental, uniform, and grand than any before discovered, while it produced works at less than one fourth of the expense”. By the end of 1795, he had produced at least fifteen illuminated books in this manner. Within some of these works, Blake created his own mythology and presented them in a prophetic format exploring his favored themes of freedom and imagination.

William Blake, Europe: A Prophesy, Title Page & Frontispiece, 1794, Library of Congress, Rosenwald Collection.

William Blake, America: A Prophesy, Title Page & Frontispiece, 1793, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Prophet

“Every man is a prophet,” Blake once wrote. This idea, at least partially, came from his love of Milton, who wrote something similar. For Blake, Milton was himself a prophet, the greatest prophet of liberty that the world had seen. Like Blake, Milton was against kings, for marriage as a union of minds, and for the individual spirit over organized religion. This was the vein in which Blake saw himself as a prophet. The poet possessed the power and responsibility of a prophet in the use of his vision and imagination. While Milton was an undeniable influence on his worldview, so too was his experience with religious nonconformity that began in his childhood. Blake believed that the Bible was “filled with Imaginations and Visions from End to End and not with Moral Virtues” from which the destinies of nations and individuals could be understood.

William Blake, Title page, To Justify the Ways of God to Man in Milton, a Poem in Two Books, 1804-1808, New York Public Library.

William Blake, Mysterious Dream, Illustration for Milton's L'Allegro and Il Penseroso, 1816-1820, The Morgan Library and Museum.

Legacy

William Blake was not a complete unknown in his time, yet he never rose to fame during his life. He had a small set of admirers, but he was dismissed by many, and for most of his career, he struggled financially. It seems there was not much profit in being a prophet, and in the years following his death in 1827, he was largely forgotten. That is, until in 1847, when his writings were rediscovered by Dante Gabriel Rossetti coinciding with a new age of political activism. His works were likewise rediscovered in the United States around that time, as he was being compared to Walt Whitman. Then, during World War I, Hubert Parry composed a song, which he called Jerusalem, yet came from the preface of Blake’s Milton. The song was a hit, used by the Suffragettes of 1917 to the present day England cricket team, and became a sort of second national anthem. Finally, Blake finally also became a major artistic figure beginning with the beat poets, when he emerged as a cult figure for the counterculture.

Interestingly, Blake prefigured the literary and artistic movement of his time, yet was always on the fringe of it. Samuel Coleridge and William Wordsworth are often credited with founding the British Romantic Movement somewhere around the beginning of the 19th century. By that point, Blake had already completed several of his illuminated books. Like Blake, these men were heavily influenced by Milton and Shakespeare, they emphasized emotion, and they valued individualism. The Romantics sought the sublime in nature and were often great travelers. However, Blake was an urban creature. Notwithstanding his three years in Felpham, he was London through and through. For Blake, it was the imagination that was infinite, and it took him far beyond England, and into eternity. William Blake’s work encompassed the great themes of the age even before Coleridge and Wordsworth’s seminal work. He embodied the spirit of the age to such an extreme that, to many, it looked like madness. It is that singularity and the scope of his genius that makes him such a fascinating figure.

Sources:

Mee, J. (2003). Blake's politics in history. In M. Eaves (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to William Blake, Cambridge (pp. 133-149). Cambridge University Press.

Ward, A. (2003). William Blake and his circle. In M. Eaves (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to William Blake, Cambridge (pp. 17-36). Cambridge University Press.

Makdisi, S. (2019). London. In S. Haggarty (Ed.), William Blake in Context (pp. 277–285). chapter, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haggarty, S. (Ed.). (2019). History, Society, and Culture. In William Blake in Context (pp. 235–344). part, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Balfour, I. (2019). Prophecy. In S. Haggarty (Ed.), William Blake in Context (pp. 113–119). chapter, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Teskey, G., & Mahoney, C. (2010). Milton and the Romantics. In A Companion to Romantic Poetry (pp. 425–441). Wiley‐Blackwell.

Sklar, Susanne M., 'Introduction', Blake's Jerusalem As Visionary Theatre: Entering the Divine Body, Oxford Theological Monographs (Oxford, 2011; online edn, Oxford Academic, 19 Jan. 2012).

Johnston, K. R. (2013). 18 Blake’s America, the Prophecy that Failed. In Unusual Suspects. Oxford University Press.

Billingsley, N. (2018). The visionary art of william blake : Christianity, romanticism and the pictorial imagination. I. B. Tauris & Company, Limited.

Katz, V. (2024). “And did those feet in ancient time”: William Blake’s Vision of…. The Poetry Foundation.

Es-vision-of-jerusalem

Blake, W., Eisenman, S. F., Crosby, M., Ferrell, E., Jacob Henry Leveton, Mitchell, W. J. T., Murphy, J. P., & And,

M. (2017). William Blake and the Age of Aquarius. Princeton University Press ; [Evanston, Il.

Crosby, M. (2009). “A Fabricated Perjury”: The [Mis]Trial of William Blake. Huntington Library Quarterly, 72(1), 29–47.

MR. BLAKE'S EXHIBITION (1809). Examiner, (90), 605-606.