Inside the Regency Country House

Home’s not merely four square walls,

Though with pictures hung and gilded:

Home is where affection calls,

Filled with shrines the heart hath builded!

-from Home Is Where There Is One to Love Us by Charles Swain (1801-1874)

Humphry Repton, Design for a Cottage Ornée in the Tudoresque Style, late 18th–early 19th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Even within the works of Jane Austen, it is apparent that there was a wide range of country houses that the Regency gentry might have inhabited. Country homes could have been modest, such as the Dashwood's cottage in Sense and Sensibility or the Austen's rectory at Steventon. In some cases, they may have been as grand as seats of nobility, such as Mr. Darcy's Pemberley in Pride and Prejudice. These upper class country homes were usually named for their architectural design or in reference to their setting, bearing the name Abbey, Hall, Court, Lodge, Manor, Park, but sometimes simply House.

Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, Bradwell Lodge, Bradwell Quay, Essex, undated, Watercolor with pen and black and gray ink, over graphite, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Those named 'Park' were usually referred to their substantial grounds, but not all homes of the gentry were part of large estates with land farmed by tenants. A fictional example of this is Hartfield belonging to the Woodhouses in Emma. This usually indicated a historically recent ascent into the class of the landed gentry. On the other hand, Mr. Knightley's Donwell Abbey is a large landed estate with tenants (like Robert Martin), and the name 'Abbey' indicates its historic characteristic. Many such monastic buildings were granted to individuals during the English Reformation and some were built as early as the 12th century.

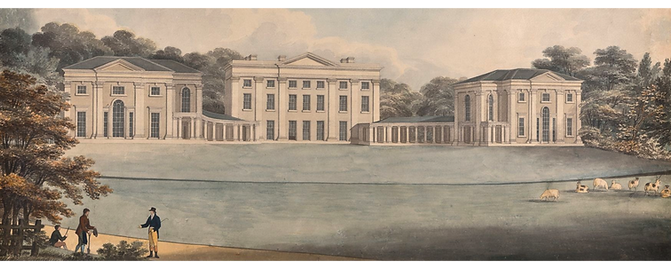

Unknown artist, Design for Stoke Park, undated, Watercolor with black ink and graphite, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

All of the above is meant to emphasize that the country house evolved over the centuries, often carrying marks of its long history upon its facade and within its walls. This is true today and would have also been true fore Regency Period inhabitants. Thus, country houses took many forms, varying in age, size, and environment. This article will focus on types of rooms and some of the odds and ends found in them. In doing so, I will not go in depth nor cover every possible room, but will try to keep to those parts of the house more common or more particular to the Regency period.

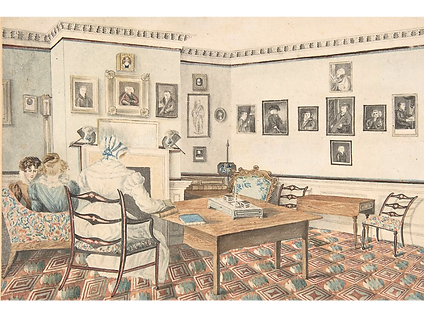

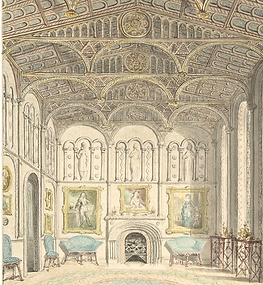

Let's begin with drawing rooms and parlors. Both are types of sitting rooms, with the drawing room being the larger and more luxurious of the two. The parlor, the more intimate and casual room, comes from the French verb parler, meaning ‘to speak’. A large house could have multiple parlors, and they might be specialized to various purposes, like a music room. Typically, the day began and ended in these rooms, and at least two sitting rooms were considered essential for respectability. Below, the images from the parsonage at Hatton and Lea Castle in Worcestershire show a range in formality, size, and grandeur.

Attributed to Granddaughters of Dr. Samuel Parr, Drawing Room at Hatton, Warwickshire, 1820-1830, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Attributed to John Carter, Drawing Room of Lea Castle Looking West, c. 1816, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

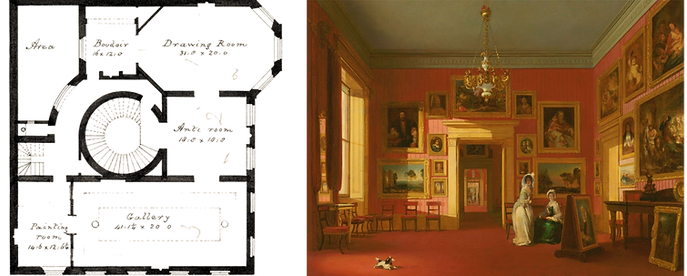

A large drawing room, like the one at Lea Castle, might be converted to a dance floor in the event of a private ball. However, the long narrow saloon (or salon) or the gallery would be more suitable to a large formal event. These terms seem a little loosely defined and overlapping. However, a gallery may have been more narrow than a saloon and would imply an emphasis on the presence of art. Below, is a floor plan of a "modest" country house that shows the dimensions of the gallery and the drawing room for comparison.

Unknown artist, Mansion of Thomas Hope Esqr. Flemish Picture Gallery, 1821, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Robert Huskisson, Lord Northwick's Picture Gallery at Thirlestaine House, between 1846 and 1847, Oil on canvas, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

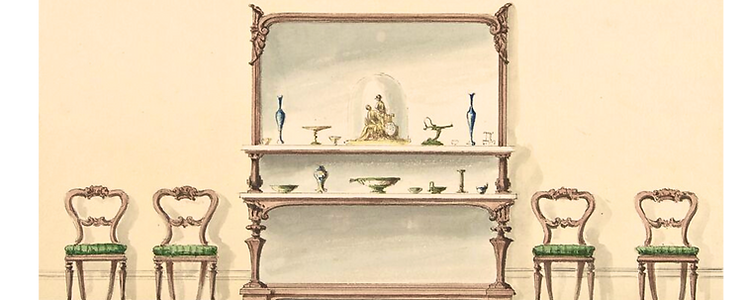

The dining room was one of the more masculine areas of the house where dark colors dominated. During the Regency period, the dining room as we know it know it now had just become firmly established as a room dedicated to meals with a table placed in the middle of it. The sideboard was another piece of furniture that had only become standard in recent decades. There food and other objects needed for service could be placed at hand.

Anonymous, British, early 19th century, Design for a Mirrored, Marble-topped Sideboard and Four Chairs, pen and ink, brush and wash, watercolor, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Some houses had a breakfast room which usually doubled as a morning sitting parlor, therefore the dining room would only be used for dinner. Following the meal, ladies would withdraw to the drawing room while men would usually remain in the dining room where they could drink, smoke, and talk about things not fit for ladies' ears. Along with the objects needed to serve dinner, one might also find within the sideboard, a chamber pot for the men's use during their after dinner frolicking.

Charles Williams, The Delicate Investigation or Secrets of - Time Three o' Clock in the Morning!!!, 1813, hand colored etching, Yale Center for British Art, The William K. Rose and Eugene A. Carroll Collection.

Bedrooms, or bedchambers, could be scattered throughout the house, but were mostly upstairs. A canopied or four-poster bed was common, with curtains to protect from chilly drafts. There might be a state bedroom for important guests in a very grand house. Servants could be spread about the house as well, either sleeping in a separate wing, in the basement, in the attic or garret, or in a combination of these areas. Regarding husbands and wives, they might share a bedroom or have separate rooms. Here, one might and wash and dress oneself as well, but there were often separate dressing rooms. The dressing room might also serve as casual sitting room and one could receive familiar guests there.

A Bed, Ackermann's Repository of arts, literature, commerce, manufactures, fashions and politics, October 1828.

Ladies Toilette, Ackermann's Repository of arts, literature, commerce, manufactures, fashions and politics, August 1809.

Chamber pots and privies were still standard. However, the most important bedrooms in the house might have water closets which had only been patented in 1778. They were still fairly novel and quite a luxury. However, chamber pots were not without novelty...nothing like a nice target for directing your efforts.

Chamber pot with bust of Napoleon, c. 1805, Staffordshire or Liverpool, creamware pot with pearlware bust, both painted in enamels, Henry Willett's Collection of Popular Pottery .

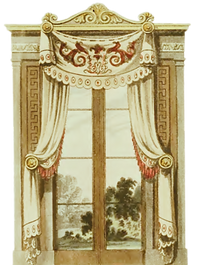

Other practical matters included heat and light, both of which centered on fire when nature did not provide them. During the Regency Period larger windows became more common, and those who updated the windows of their homes could experience a greater deal of natural light. In the 18th century more and more old casements, which opened outward, were being replaced by taller sash windows, which slid up and down. Bay venetian, and French windows were wonderful for adding architectural flare, but windows were expensive for two reasons. The glass itself was costly and there was a tax on windows.

John Buckler, South West View of Ingestre, Staffordshire; the Seat of the Right Honourable Earl Talbot, 1815, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Rudolph Ackermann, Library Window Curtain, Repository of arts, literature, commerce, manufactures, fashions and politics, January 1815.

However, fire was essential for light in the evening as well as for warmth. Most lighting in the evening came candles (one of the major expenses of the household). Candles varied in the quality of light and smell. Tallow candles, a byproduct of beef and mutton, were the most widely used since they were the cheapest. Wax candles were preferred because they produced better light and less odor, but they were more expensive. Lamps were another source of light during the Regency period. They had their disadvantages at first. Oil lamps often used fish oil, which smelled, and early lamps could be dim, but during the Regency period the Argand lamp (invented in 1784) came into more common use, which was brighter than any other source of artificial light. The Gothic lamp pictured here was intended to contain six Argand lamps.

Gothic Lamp for a Hall, Ackermann's Repository of arts, literature, commerce, manufactures, fashions and politics, August 1825.

Virtually all rooms had fireplaces, and the kitchen generally had the largest fireplace. One innovation in this area during this period was the Rumford stove, which was not a stove in the sense we might think of, but a modified fireplace. The design helped send more heat into the room rather than up the chimney and lengthened the time it took to consume fuel. While hallways were the coldest parts of the house even different parts of a room could vary greatly in heat. Fire screens were used to shield a person from the heat or the light of a fireplace. They might be small or a could be a larger folding screen. The fire screens below came "blank" with the expectation that one of the females of the house would cover the screen with a painting of her own.

Firescreens, Ackermann's Repository of arts, literature, commerce, manufactures, fashions and politics, December 1815.

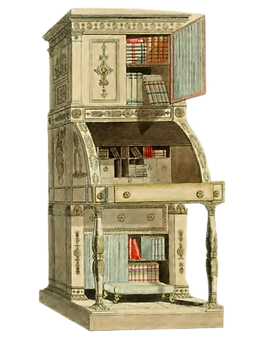

Among the other rooms on the principal floor of the house was the library. The gentleman's library communicated taste, discernment, and learning. Libraries grew during the Georgian period along with the cultural emphasis on intellectual pursuits. The library was expected to have books that covered such subjects as law, agriculture, parliamentary debates, math, antiquaries, architecture, and poetry and plays. Many of these books would have been collected over generations, but novels had just begun to find their way into home libraries during the Regency. During this time, the library became more widely used by the family at large.

Secretaire Bookcase, Ackermann's Repository of arts, literature, commerce, manufactures, fashions and politics, April 1822.

Library Table and Chair, Ackermann's Repository of arts, literature, commerce, manufactures, fashions and politics, January 1814.

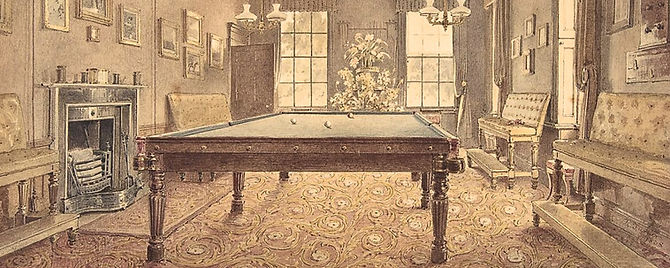

There was often a room dedicated to billiards which had been around for about two hundred years, and early on, was played by both men and women. It was not until early in the nineteenth century that specific spaces were designated as billiard rooms. These rooms developed into male-dominated areas that were often decorated in simple and neutral tones with wood panelling.

Reid Turner, Interior of the billiard room at Lupton House, Devonshire, designed by George Wrightwick for Sir J.B.Y. Buller, 1838, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Conservatories in country houses became increasingly popular toward the end of the eighteenth century. A conservatory is a room or structure attached to the house that was characterized by very large windows, on at least two sides. This glassed-in space was plant-filled and allowed enjoyment of the country setting, blurring the boundary between the indoor and the outdoor.

Sir Jeffry Wyatville, 1766–1840, Conservatory at Thoresby Hall, undated, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Below stairs or in a separate wing, you would find the kitchen, always positioned for safety and practicality. Many other rooms dedicated to service, such as the scullery, larder, laundry, brewhouse, and bakehouse were placed adjacent to the kitchen.

Thomas Rowlandson, The Squire's Kitchen, ate 18th–early 19th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

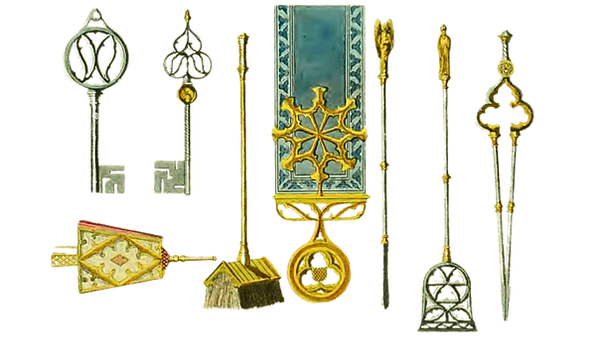

Among these rooms was also the servants hall, where servants gathered and ate their meals. Here, there was usually a row of bells along the wall which could be rung from different parts of the house in order for servants to be beckoned with ease. From there servants would be dispensed to fulfill all of the daily chores of maintaining the country house and serving its more fortunate owners.

Gothic Utensils (keys, hearth-broom, bell-pull, &c.), Ackermann's Repository of arts, literature, commerce, manufactures, fashions and politics, September 1827.

Sources:

Findlen, P. (Ed.). (2021). Early modern things : objects and their histories, 1500-1800 / edited by Paula Findlen. (Second edition.). Routledge.

Stobart, J., & Rothery, M. (2016). Consumption and the Country House (First edition.). Oxford University Press.

Stobart, Jon, and Mark Rothery, 'Practicalities, Utility, and the Everydayness of Consumption', Consumption and the Country House (Oxford, 2016; online edn, Oxford Academic, 18 Aug. 2016).

Lowry, E. (2020). Household textiles 1660-1850: hidden items of material culture from the country house. Family & Community History, 23(2), 95–118.

Rule, J. (2014). Albion’s people : English society, 1714-1815 / John Rule. Routledge.

Woodforde, J. (2023). The Parsonage. In Georgian Houses for All. Taylor & Francis Group.

Trevor Yorke. (2012). The English Country House Explained. Countryside Books.

Edwards, C. (2024). Billiard Rooms. In Nineteenth-Century Interiors (1st ed., Vol. 3, pp. 185–186). Routledge.

Tropp, R. (2021). “The most original and interesting part of the design”: The attached quadrant conservatory at the dawn of the nineteenth century. Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes, 41(3), 234–256.

Olsen, Kirstin. All Things Austen. Greenwood, 2005.

Austen, Jane, and David M Shapard. The Annotated Emma. Anchor Books, 20 Mar. 2012.

Austen, Jane, and David M Shapard. The Annotated Pride and Prejudice. Anchor Books, 2012