Old Price Riots: Panic at the Theatre!

Hard is his lot, that here by Fortune plac’d,

Must watch the wild vicissitudes of taste;

With ev’ry meteor of caprice must play,

And chase the new-blown bubbles of the day.

Ah! let not censure term our fate our choice,

The stage but echoes back the public voice.

The drama’s laws the drama’s patrons give,

For we that live to please, must please to live.

From Drury-lane Prologue Spoken by Mr. Garrick at the Opening of the Theatre in Drury-Lane, 1747

By Samuel Johnson

Early morning, September 20, 1808, flames lit up the London sky. The fire that originated near the ceiling of the Covent Garden theatre burned fiercely. The fire attained great height and roared furiously while the local people scrambled to retrieve the floating flakes of fiery debris that landed about their properties in order to prevent a conflagration that could engulf the entire neighborhood and beyond. People stood atop London’s other patent theatre, Drury Lane, ready to open the immense reservoir of water that was kept there. They rushed about stuffing the windows with wet cloth, and they succeeded in keeping that temple of dramatic spectacle from suffering the fate of their rival, Covent Garden…on that day. However, within five months Drury Lane would also go down in flames.

_edited.png)

from James Gillray, Counsellor O.P, - defender of our theatric liberties, 1809, British Museum.

from John Bluck, Fire in London, 1808, Yale Center for British Art.

Covent Garden theatre lay in ruins after that day. The uncontainable fire took the lives of thirty individuals and left the building completely consumed. Gone as well were the theatre’s vast collection of sets and wardrobes, original manuscripts from Handel, and his celebrated organ (worth over £1,000). The task before the owners, who included renowned actor John Philip Kemble, was to raise the funds to start anew.

from James Gillray, New Dramatic Resource _a Begging we will go!_a Scene from Covent Garden Theatre after the Conflagration' and 'Theatrical Mendicants relieved - have Pity upon all our Aches and Wants!', 1809, British Museum

In addition to the insurance settlement, which amounted to about half of the funds needed to replace the original 1733 theatre (enlarged in 1792), other money received included a sum of £10,000 from the Duke of Northumberland, £1,000 from the Prince of Wales, and subscriptions at £500 per share. With these funds in hand, the owners were on their way to rebuilding and making their theatre even better than before.

William Daniell, 1769–1837, British, View of the East Front of the New Theatre Royal Covent Garden, 1809, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

The architect was Robert Smirke, who would also go on to design the Neoclassical façade of the British Museum. The new theatre was Classical in concept, taking inspiration from the Parthenon while sporting fluted columns, bas-relief panels, and allegorical statues. The interior was lavishly decorated and could now seat 3,000 people. Wonderful to behold, for sure! Perhaps, not. We shall soon see how the new design became an important point of contention.

John Bluck, British, New Covent Garden Theatre, 1810, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

On Monday, September 18, 1809, the new theatre would have its grand opening. The playbills for that night advertised a performance of Macbeth…and entreated the “enlightened liberal public” to understand that higher prices would be required for admittance due to the cost of rebuilding. Afterall, the theatre had not raised its prices for decades and the increase would be fairly small (10-15%).

Artist Unknown, published by Walker, A parody on Macbeth's soliloquy at Covent Garden Theatre, 1809, Library of Congress.

Yet, as soon as Kemble took the stage, the audience began to unleash its resentment. They called for the old prices. Kemble pleaded his case, and in his mind imploring to reason with statements like “solid our building, heavy our expense,” but he was mercilessly drowned out by hooting and hisses. The audience replied with shouts of “No imposition - no extortion!” This lasted throughout the evening until, near the end of the performance, the authorities arrived and read the Riot Act. They emerged through the stage’s trap doors, almost as though they were part of the performance, pointing fire hoses at the audience.

George Cruikshank, Acting magistrates committing themselves being their first appearance on this stage as performed at the National Theatre Covent Garden, September 18, 1809, British Museum.

They were warned in no uncertain terms, for the maximum penalty for violating the Riot Act was death, and Kemble held hope that normalcy would resume on the following night…but that was not to be. The discontented audience returned. This time with the letters "O.P." displayed by many of the aggrieved. O.P. would become the symbol and the label for the rioters and their supporters, appearing on hats, handkerchiefs, fans, and waistcoats.

Isaac Cruikshank & George Cruikshank, The OP spectacles, 1809, British Museum.

On that second night, a large banner was unfurled from one of the boxes with “Old Prices!” written across it. Still, the owners would barely acknowledge the protestors, and the next morning the Times wrote, “If the Managers are deaf to a voice which stuns every other ear with its loudness and decision, we suppose they will not be so blind as to act to empty benches…”

Above images from Thomas Rowlandson, This is the House that Jack Built, 1809, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

J. Pitts (publisher), A View of Drury Lane Theatre on Fire, 1809, Victoria & Albert Museum.

But, there would not be empty benches. For sixty-seven nights the pit would be filled (though sometimes not until the third act when half-price admission began) with a raucous protest against the new prices. Yes, the price increase rankled much of the Regency London rank and file, but there were other factors at play. For one, Covent Garden was one of only two patent theatres in London. The other patent theatre was Drury Lane, which coincidentally also burned down only months its rival. Within this context, one person wrote to the editor of the Constitutional Review that “theatres in a country under a monarchical form of government can never be considered as private property, but as a great national concern.”

Furthermore, the enlarged theatre made the new seating arrangements less agreeable for most of its patrons. For instance, the gallery was smaller, further away, and broken up by arches that made the viewing more akin to peering from pigeonholes. It was now difficult to hear and see the performance.

Thomas Rowlandson, Pidgeon Hole. A Convent Garden Contrivance to Coop up the Gods, 1811, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

One of the reasons the layout of the new theatre was contrived so was to accommodate more private boxes for the wealthy, which would provide more income for the proprietors. This seemed to be even more of an affront, for there seemed to be a realignment of the relationship between the aristocracy and the common man. The theatre had traditionally brought together the disparate and otherwise separated classes of British society. Now, there was a separate entrance for those with private boxes, with a private staircase and anteroom. This was further seen by the O.P’s to be promoting the immoral behavior by the upper class. In this new arrangement, they had plenty of privacy to enable the aristocracy to evade the scrutiny of the public as they consorted with prostitutes and mistresses.

Feeding this vocal outrage was the context of the place and time. The theatre was located in Covent Garden in Westminster, which was home to a disproportionately large number of enfranchised men. It was one of the few places in all of Britain where every man who paid the poor rate had the vote whether a householder or not. That meant that men who frequented this theatre felt empowered to protect their rights.

John Bluck, A Bird's Eye View of Covent Garden Market, 1811, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

In general, the population was feeling, perhaps more than ever, that the powers that be needed to be held to account for the state of the nation. Britain had been mired in war with France for over 15 years. As a result, the people had been subject to rampant inflation, and of course, suffered the heavy burden of the human toll from the battlefields. The fallout from the disastrous Walcheren Expedition was fresh on the minds of the people. Poor planning in an attempt to take Antwerp had led to the death of 4,000 men from fever with many more casualties at a whopping cost of £501,101.

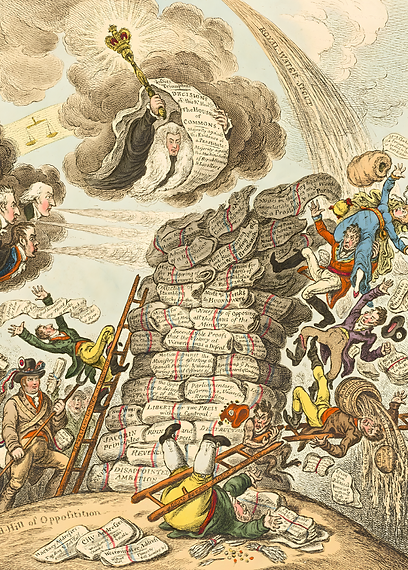

James Gillray, Overthrow of the Republican-Babel, 1809, Art Institute Chicago.

Furthermore, the year 1809 had begun with the Mary Clarke Affair. Mary Clarke was the on-again, off-again mistress of the Duke of York, a younger son of King George II. Her testimony exposed a scandal involving corruption of the monarchy, the armed forces, and the clergy. It dominated newspapers, prints, and pamphlets for the first half of the year, and no doubt, many people were disillusioned with the corruption and immoral behavior of the upper echelons of society.

Surely, it would be understandable if Britons were on edge and ready to defend what they considered to be a basic right. Unfortunately for John Philip Kemble, as the most visible of the owners, he bore the brunt of the attacks. Born to a family of “strollers”, a traveling acting troupe, he had humble beginnings, but was now seen as a symbol of oppression. Kemble did not help his cause when for six nights he hired a group of boxers, or “bruisers”, to try to deter the rioters. The fact that most of the boxers were Jewish and Irish was even more of an outrage. Kemble was pilloried in the press and had windows broken at his home. The O.P. War had become quite the battle of wills.

Isaac Cruikshank, Set a beggar on horseback & he'll ride to the Devil!!!, 1809, British Museum.

The disturbances not only persisted, but became more creative. Beyond bringing various noisemakers, the members of the pit began to put on their own performances. There had always been a give and take between the audience and the stage. Unlike modern theatres, the audience was not darkened, so they could be seen just as well as those on the stage. And now, the pit became the stage. These counter-performances included races, mock fights, and singing. Finally, in the late stage of the riots, the protestors resorted to throwing food and other objects onto the stage.

Published by S W Fores, Imitation Bank Note, 1809, British Museum.

Thomas Rowlandson, The boxes, O woe is me, t'have seen what I have seen seeing what I see, 1809, Folger Shakespeare Library.

One can only imagine how John Philip Kemble had envisioned the opening of the new Covent Garden Theatre, but this was surely nothing like. Finally, on December 14, after months of disturbances and being villainized in the press, he found himself arriving at the Crown and Anchor Tavern, a known haunt of local radicals. There, he met with the members of the O.P. Committee, and came to terms with its leaders to put an end to the ordeal.

The O.P.’s were victorious with most of the old prices restored and a promise that the number of private boxes was to be reduced for the next season. With no significant damage to the theatre and minimal violence, riot is almost a misnomer. However, in their unique protest, the O.P’s usurped the theatre’s purpose as purveyors of drama in order to communicate their displeasure. Thus, the stage had no choice but but to echo back the public voice.

Baer, M. (1992). Theatre and disorder in late Georgian London. Clarendon.

DESTRUCTION OF COVENT GARDEN THEATRE. (1808). Examiner, (39), 621-624.

DESTRUCTION OF COVENT GARDEN THEATRE BY FIRE. (1808). Cabinet, Or, Monthly Report of Polite Literature, 1807-1808, 4, 278-283.

McEvoy, S. (2016). The Drama’s laws the Drama’s Patrons give: The Covent Garden Old Price riots of 1809. In Theatrical Unrest (1st ed., pp. 49–66). Routledge.

Baker, H. C. (2014). John Philip Kemble : The Actor in His Theatre / Herschel C. Baker. (Reprint 2013). Harvard University Press.

McPherson, H. (2002). Theatrical Riots and Cultural Politics in Eighteenth-Century London. The Eighteenth Century, 43(3), 236–252.

DESCRIPTION OF THE ISLAND OF WALCHEREN. (1809). La Belle Assemblée : Or Court and Fashionable Magazine, 7, 37–37.

Sutcliffe RK. 1809: A Year of Military Disappointments. In: British Expeditionary Warfare and the Defeat of Napoleon, 1793–1815. Boydell & Brewer; 2016:195-213.

Baker, J. (2017). Scandal. In: The Business of Satirical Prints in Late-Georgian England. Palgrave Studies in the History of the Media. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Hadley, E. (1992). The Old Price Wars: Melodramatizing the Public Sphere in Early-Nineteenth-Century England. PMLA : Publications of the Modern Language Association of America, 107(3), 524–537.

ACCOUNT OF THE OPENING OF COVENT-GARDEN THEATRE. (1809, October). La Belle Assemblée : Or Court and Fashionable Magazine, 7(50), 122-127.

Police - Covent Garden Theatre, Persons for Disturbance. (1809, September 20). The Times.

Theatres &c. - Covent Garden, Letters on. (1809, September 23). The Times.