Pugnacious Pugilists of the Regency Period

His glossy and transparent frame,

In radiant plight to strive for fame!

To look upon the clean shap'd limb

In silk and flannel clothed trim;—

While round the waist the kerchief tied

Makes the flesh glow in richer pride.

'Tis more than life,—to watch him hold

His hand forth, tremulous yet bold,

Over his second's, and to clasp

His rival's in a quiet grasp;

![Charles Turner, 1774–1857, [Boxing] Mr. John Jackson. From am original in the possession of Sir Henry Smyth., 1810, Mezzotint, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1985.36.699. (3).png](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/18d2f2_5d51c96d7655488da68328a5510d3c22~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_626,h_353,al_c,lg_1,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/18d2f2_5d51c96d7655488da68328a5510d3c22~mv2.png)

To watch the noble attitude

He takes,—the crowd in breathless mood;—

And then to see, with adamant start,

The muscles set,—and the great heart

Hurl a courageous splendid light

Into the eye,—and then,—the fight!

-from What Is Life? Lines To ------

by J.H. Reynolds

from artist unknown, published by IB Brookes, Lex talionis or hit the first, 1831, British Museum.

Two men stand toe to toe, bare fists raised, violence batters the beautiful bodies…and they are enveloped by the cheers, jeers, and gasps emanating from the men who watch, men from every segment of British society, from the Prince of Wales to the most humble chimney sweep. This could have been a description of a scene from a Regency boxing match, and what a scene it would have been! Yes, it was a popular pastime...but it was so much more.

from Thomas Rowllandson, Rural Sports, A Milling Match, 1811, British Museum.

Bare-knuckled pugilism rose and fell and rose again in a see-saw of popularity through the 18th century before settling in to its heyday from a period from about 1790 - 1820. England long had a fascination with violent spectacle. For example, from medieval times, bear and bull-baiting were popular entertainments that involved staged fights between the named animal and several trained dogs. In the early 18th century, the proprietor of a London “Bear Garden” was killed and devoured by one of his bears. This was one incident that prompted the focus of violent entertainment to shift towards human combat.

![Charles Turner, 1774–1857, [Boxing] Mr.](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/18d2f2_de0f3ee2e08f473fbc4ca854c781d36a~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_621,h_383,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/Charles%20Turner%2C%201774%E2%80%931857%2C%20%5BBoxing%5D%20Mr_%20.png)

Henry Thomas Alken, The country squire taking a peep at Charley's Theatre Wesminster,..., 1799-1851, British Museum.

Boxing itself was technically illegal, but the sport caught the interest not just of the lower orders but the aristocracy as well (which is probably what led the government to look the other way). A subculture developed around boxing with its own unique jargon referred to as the ‘flash’. Though the jargon may have originated with the lower classes, the sport was carried to new heights by the gentlemen of ‘the Fancy’ who were a fraternity of boxers, moneyed and often aristocratic gamblers, patrons, and amateur devotees. While “The Fancy” included the upper echelons of society, the prizefighters themselves were not of these classes. They were usually laborers and tradesmen who depended on their upper body strength, most especially butchers and blacksmiths.

![Charles Turner, 1774–1857, [Boxing] Mr. John Jackson. From am original in the possession of Sir Henry Smyth., 1810, Mezzotint, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1985.36.699. (1).png](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/18d2f2_cdd8e01495e746dd92be1aa7f7391dff~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_464,h_337,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/18d2f2_cdd8e01495e746dd92be1aa7f7391dff~mv2.png)

from William Dent, published by James Aiken, Lord B- boxing a Butcher at Brighton, 1791, British Museum

These disparate backgrounds each found something to their advantage in boxing. Fighters depended on the financial backing of rich patrons and wealthy gentlemen saw opportunities in gambling and the desire to learn how to fight. It was not only the unlikely amalgamation of people from different backgrounds that occurred, but there was also a constellation of seemingly unrelated ideas that revolved around boxing. Although boxing would never overcome the criticism of its inherent violence and association with excess, "Britishness" and "manliness" became largely defined by, and in turn, came to characterize boxing itself. In the late 18th century, worries grew of spreading effeminacy among British men due to increased wealth and foreign influence. What is more, this was paired with the embarrassment of losing the American colonies, disquiet in Ireland, facing the spectre of political unrest at home, and growing tension with France. Through British pugilism, they sought to differentiate themselves from what they viewed as effeminate Frenchmen.

![Charles Turner, 1774–1857, [Boxing] Mr.](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/18d2f2_6c2d96190b60451592f23ab17d8f9372~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_503,h_375,al_c,q_80,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/Charles%20Turner%2C%201774%E2%80%931857%2C%20%5BBoxing%5D%20Mr_%20.jpg)

After James Gillray and John Nixon, Politeness, after 1780, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This political unrest arose largely from the influence of and the fear of revolutionary ideas from France. The need for manly British fighters was firmly established when war with France commenced in 1792, and the art of pugilism became a matter of national importance. Boxing's lessons would help English armies prevail. This British boxing ethos was securely in place until after the defeat of Napoleon.

![Charles Turner, 1774–1857, [Boxing] Mr. John Jackson. From am original in the possession of Sir Henry Smyth., 1810, Mezzotint, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1985.36.699. (3).png](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/18d2f2_2928205874164dddaec1e466851377d2~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_627,h_355,al_c,lg_1,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/18d2f2_2928205874164dddaec1e466851377d2~mv2.png)

James Gillray, 1756–1815, Fighting for the Dunghill, - or - Jack Tar Settling Citoyen Francois, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Boxing brought together rich and poor, Black and White, Jew and Protestant to admire the beauty of the pugilist and the brutal art that broke and battered bodies. It reflected the increasing social mobility of the time and class fluidity as men from distinct and often separate segments of society came together to celebrate what they viewed as the pinnacle of Britishness and manliness. It long survived the arguments put forward by evangelical reformers since the late 18th century that brutal sports led to moral and spiritual disorder. However, as the Victorian period approached, a new wave of moral puritanism brought a change in tastes and boxing’s popularity waned. The golden era came to an end and the sport’s popularity declined in Britain, but its form of pugilism would spread around the world and continue to have its influence at home.

It became not only acceptable, but laudable, for a gentleman to learn the art of pugilism. The Prince of Wales and Lord Byron both took lessons from renowned prizefighters. Any student would have learned that the fundamental foundations of the sport were ‘wind’ (endurance), ‘science’ (technique), and ‘bottom’ (courage). These ideas were pursued at a time when the cult of sensibility juxtaposed a keen rise in regard for the fighting spirit of the British bulldog. The soul of the poet met the profoundly physical end of a fist. However, I doubt that Lord Byron's sparring ever came anywhere near the actual brutality of a true prizefight.

![Charles Turner, 1774–1857, [Boxing] Mr. John Jackson. From am original in the possession of Sir Henry Smyth., 1810, Mezzotint, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1985.36.699. (4).png](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/18d2f2_511100c94cd74723851a247baf6ef55b~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_477,h_355,al_c,lg_1,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/18d2f2_511100c94cd74723851a247baf6ef55b~mv2.png)

Thomas Rowlandson, Six Stages of Marring a Face, 1792, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Let’s have a look at some of the most significant prizefighters who carried the sport to its zenith as well as those pugilistic personalities that featured in its Regency golden age.

John "Jack" Broughton (1703-1789)

Before becoming a professional boxer, Broughton was a waterman, carrying passengers along the River Thames. He held the title of champion for over a decade and it was Broughton's Rules that first codified boxing, remaining in effect until 1838. Opening his own arena and school, he was able to capitalize on his substantial fame beyond all boxers that came before him. Importantly, he also introduced large padded gloves, or mufflers, which made boxing more attractive to a wider audience, most especially, his upper class students. Broughton is said to have died with £7,000, a fortune for a one-time waterman.

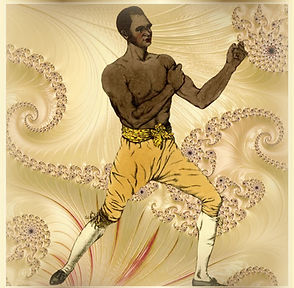

Bill Richmond (1763-1829)

He was the first American prizefighter and black sports star in England. Born into slavery, Richmond left New York as a (free) servant to General Hugh Percy. After accumulating a series of wins over larger and more experienced fighters, his ascendance in boxing presented a challenge to notions of racial hierarchy and English nationalism. Furthermore, his dance-like footwork and side-stepping incited criticism for not taking blows in the manner of an Englishman. In the end, he was recognized as one of the foremost experts of the pugilistic science and revolutionized the sport.

Daniel Mendoza (1764-1836)

He had attempted a number of professions before prizefighter: greengrocer, tobacconist, and glazier. However, Mendoza was continually drawn into fights, usually involving the honor of a woman or Judaism. He was not a large man, but like Bill Richmond, he had an impressive combination of agility, speed, and technique. In fact, he published two books on the art of boxing. Often referred to simply as "The Jew", he was also criticized for his unwillingness to stand firm in the style of a true Brit and was referred to as 'cunning'. Nonetheless, he became a celebrity, and in a 1790 bout with John Humphreys he was praised for his humanity when, instead of laying into his opponent when he had become helpless, Mendoza gently laid him down to the ground to end the fight. He held the title of champion from 1791-1794.

John Jackson (1769-1845)

Jackson competed in relatively few high profile matches. In fact, his third and last battle, was with Mendoza, who he quickly defeated. During his short prizefighting career, he was fortunate enough to receive the patronage of the Prince of Wales and was even asked to be a page and organize 17 other prizefighters at the coronation that would transform the Prince Regent into King George IV. Believed by many to be the perfect physical specimen of a man, he was said to be the model for Thomas Lawrence's 1797 painting, "Satan Summoning his Legions". He also had a school that catered to aristocrats such as the Lord Byron, who also frequented Bill Richmond's school. Byron wrote in his 1811 poem 'Hints from Horace' that "men unpracticed in exchanging knocks/Must go to Jackson ere they dare to box."

Tom Molineaux (1774-1818) and Tom Cribb (1781-1848)

I write of these two boxers together, for they had two of the most highly attended and written about matches of the Regency Period. Tom Molineaux was born into slavery in Virginia, and it is believed that he fought his way to freedom by defeating a slave from another plantation in a match arranged by the respective owners. He made his way to New York where there was a thriving pugilistic culture among its black inhabitants. It seems he then sailed to England with ambitions of becoming the champion in the country where boxing was held in the highest regard.

In his teens, Tom Cribb worked as a coal porter and spent some time at sea. In his first prizefight in 1805, he went seventy-six rounds to defeat his opponent and was named 'champion' by 1809. He would clearly be Molineaux's target when he set sail for England.

Tom Molineaux quickly sought out Bill Richmond to train him. He made short work of his early opponents in England. Unrivaled, Cribb had been on the verge of becoming a coal merchant, but Molineaux's challenge changed his plans. On December 18, 1810, the much anticipated event took place on a cold and rainy day. Cribb was victorious, but there were some who that Molineaux had not been treated with fairness. For example, at one point a mass of spectators rushed the ring and he had a finger broken as he was surrounded by the mob.

A second fight occurred in September of the following year, for which it is said that Cribb trained thoroughly...and Molineaux did not. There were about 20,000 excited spectators in attendance, but this time, the match was shorter and Cribb was the clear winner.

The fights were celebrated in print, by having the pair's likenesses stamped upon pottery, and through being reproduced as porcelain figurines. However, unlike some of their most prominent predecessors, these two boxers did not live prosperous lives after their prizefighting days ended. For Molineaux, money was made but spent just as quickly, and he drank heavily. He was dead by 1818. Cribb lived longer, but with multiple businesses failing, he died with debts. An American would not travel to England again to challenge the champion until 1860 when John Camel Heenan fought Tom Sayers.

from Robert Cruikshank, The Battle Between Cribb and Molineaux, September 28, 1811, Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Egan, Pierce, 1772-1849, Key to the picture of the fancy going to a fight at Moulsey-Hurst, 1819, Yale Center for British Art.

During the Regency period, boxing and its heroic fighters were glorified in the writing like never before. It was central to a burgeoning sports journalism. The leading figure of this group was Pierce Egan whose “Boxiana”, a series of articles dedicated to the pugilistic art, was written from 1812 to 1829. It is evident with what extreme regard boxing was held by many when he wrote of boxing’s origins in a manner that evokes a Genesis-like reverance:

“Originally, little doubt can exist, when every man stood on the alert to provoke or resist an insult, he fought without system, and with naked fist ; but soon rules were laid down, and these natural means of attack or defence submitted to peculiar regulations, the collection of which became a DISCIPLINE, a SCIENCE, and an ART. A discipline, because it was taught for the benefit of the respective individuals ;-a science, on account of the necessary trainings, before the acquisition of expertness ; - and an art with respect to the different studies it presupposed. Consequently, in order to give a better opportunity to the boxers to show their skill, by protracting the temporal length, or duration of their exertions, strong armour for the head and hand was invented. This circumstance gave rise to two sorts of boxing. The first, when the champions had no other arms than their natural strength and agility ; the other, when they made use of the amphotides and cæstus.”

![Charles Turner, 1774–1857, [Boxing] Mr. John Jackson. From am original in the possession of Sir Henry Smyth., 1810, Mezzotint, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1985.36.699. (6).png](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/18d2f2_19b12b2e1c194b72b7cad147c6410f25~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_592,h_333,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/18d2f2_19b12b2e1c194b72b7cad147c6410f25~mv2.png)

Three segments from Cruikshank, Robert, 1789-1856, Going to a fight : the sporting world in all its variety of style and costume along the road from Hyde Park Corner to Moulsey Hurst, 1819, Yale Center for British Art.

Although boxing was very popular with the high and low ends of society, it was less so with the middle and intellectual sort. Hence, the significance of the William Hazlitt piece, “The Fight”. He wrote this piece in 1822 for his magazine which generally appealed to the latter sort. An amazing 25,000 spectators are said to have attended this fight in the countryside between Misters Neate and Hickman, who were not among the top echelon of Regency prizefighters. He was quite taken with the excitement and joviality of the event, and even the respectability of the its spectators. In his attempt to counter the moral repugnance many of his readers felt towards the boxing world, Hazlitt even began by dedicating “The Fight to his female readership, saying, “Think, ye fairest of the fair, loveliest of the lovely kind, ye practisers of soft enchantment, how many more ye kill with poisoned baits than ever fell in the ring; and listen with subdued air and without shuddering, to a tale tragic only in appearance, and sacred to the FANCY!”.

Still, Hazlitt could not exonerate boxing of its more notorious characteristics. While some spectators loved the sport for the thrill of seeing the violent spectacle of hand-to-hand combat, others found more exhilaration in the practice of gambling which invited corruption. The sport had increasingly come to be associated with criminal activity and corruption.

Boxing brought together rich and poor, Black and White, Jew and Protestant to admire the beauty of the pugilist and the brutal art that broke and battered bodies. It reflected the increasing social mobility of the time and its class fluidity as men from distinct and often separate segments of society came together to celebrate what they viewed as the pinnacle of Britishness and manliness. Boxing long survived the arguments put forward by evangelical reformers since the late 18th century that brutal sports led to moral and spiritual disorders. However, as the Victorian period approached, a new wave of moral puritanism brought a change in tastes and boxing’s popularity waned. The golden era came to an end and the sport’s popularity declined in Britain, but its form of pugilism would spread around the world and continue to have its influence at home.

George Cruikshank, Representation of the Elegant Silver Cup Presented to Cribb, from Pierce Egan's Boxiana; or Sketches of Ancient and Modern Pugilism, 1812, British Museum.

Sources:

Egan, P. (1829). Boxiana, Or, Sketches of Ancient and Modern Pugilism: Comprising the Only Original and Complete Lives of the Boxers. United Kingdom: Sherwood, Neely, and Jones.

Eaker, A. (2024). The Art of Marring a Face: Exhibiting Boxers in Georgian London. The Huntington Library Quarterly, 87(2), 165–182.

WRIGHT, J. M. (2017). Cosmopugilism: Thomas Moore’s Boxing Satires and the Post-Napoleonic Congresses. Studies in Romanticism, 56(4), 499–523.

Ungar, R. (2011). The Construction of the Body Politic and the Politics of the Body: Boxing as Battle Ground for Conservatives and Radicals in Late Georgian England. Sport in History, 31(4), 363–380.

Waite, K. (2014). Beating Napoleon at Eton: Violence, Sport and Manliness in England’s Public Schools, 1783-1815. Cultural and Social History, 11(3), 407–424.

Harrow, S. (2015). Chapter 7: Boxing for England: Daniel Mendoza and the Theater of Sport. In British Sporting Literature and Culture in the Long Eighteenth Century (1st ed., pp. 152–178). Routledge.

Boddy, K. (2008). Boxing: a cultural history (1st ed.). Reaktion Books Ltd.

Downing, K. (2008). The Gentleman Boxer: Boxing, Manners, and Masculinity in Eighteenth-Century England. Men and Masculinities, 12(3), 328-352.

O’Quinn, D., & Youngquist, P. (2013). In the Face of Difference: Molineaux, Crib, and the Violence of the Fancy. In Race, Romanticism, and the Atlantic (1st ed., pp. 213–235). Routledge.

Day, D. (2012). “Science”, “Wind” and “Bottom”: Eighteenth-Century Boxing Manuals. International Journal of the History of Sport, 29(10), 1446–1465.

Obi, T. J. D. (2009). Black Terror: Bill Richmond’s Revolutionary Boxing. Journal of Sport History, 36(1), 99–114.

JOHN WHALE. (2018). Writing Fighting/Fighting Writing: Jon Badcock and the Conflicted Nature of Sports Journalism in the Regency. In ALEXIS TADIÉ & DANIEL O’QUINN (Eds.), Sporting Cultures, 1650–1850 (p. 179). University of Toronto Press.

Chill, A. (2017). Bare-Knuckle Britons and Fighting Irish: Boxing, Race, Religion and Nationality in the 18th and 19th Centuries. United States: McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers.

Moore, J. (2013). Modern Manners: Regency Boxing and Romantic Sociability. Romanticism (Edinburgh), 19(3), 273–290.

Mitford, J. (1845). MR. JACKSON, THE PUGILIST. The Gentleman’s Magazine: And Historical Review, July 1856-May 1868, 24, 649–649.

Cone, C. B. (1982). The Molineaux-Cribb Fight, 1810: Wuz Tom Molineaux Robbed? Journal of Sport History, 9(3), 83–91.

Magriel, P. (1951). Tom Molineaux. Phylon (1940-1956), 12(4), 329–336.

Cavendish, Richard (1998). Death of Tom Cribb. https://www.historytoday.com/archive/death-tom-cribb.